Beware – Shallow curve ahead.

I’m willing to lend you 10 bucks, but I’ll expect some interest from the loan.

I’m willing to lend you 10 bucks, but I’ll expect some interest from the loan.

Now, just how much interest I’m going to charge is going to be based upon a few things. Obviously, if I know you well, and feel you aren’t going to stiff me, I’m going to charge less interest than if you come across as ‘shady’; If you’re wearing white socks with a suit, count on a pretty high rate. But, there are other factors that I’ll be taking into consideration before Alexander Hamilton moves from my wallet to yours.

A major consideration I’ll take into account is: How long until you’re going to pay me back? If you’re going to get the 10 bucks back to me next week (and are wearing properly colored socks), the interest rate will be low. But if you’re not going to be paying me back for, say, another 10 years, I’m going to want more interest. One reason for this is that I’m now adding almost 10 years during which you might actually become sketchier. But, the major issue here is this: I can invest that money over a longer period of time with a good chance at a better return than what I’d get on a low-interest loan.

This dynamic of lower interest rates for short-term loans and higher interest rates for longer-term loans normally plays itself out across the financial world. A 10-year mortgage generally has lower interest than a 30-year mortgage. CDs (which are basically you lending money to the bank) work the same way: 1-year CDs return a lower amount than 5-year CDs. And, if you loan money to the federal government (by purchasing a ‘Treasury Bill’ or a ‘Treasury Note’), you’re usually rewarded with higher yields on the longer ones than the shorter ones.

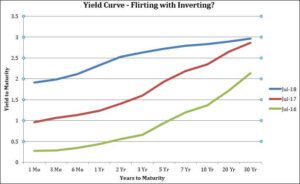

These rates can be tracked on a graph. The resulting plots of data over a range of years are called the ‘Yield Curve’. It’s easy to see where the yield curve gets its name when you look at the red and green curves on our chart (July 2017 and July 2016 curves). As maturities lengthen, the yield on these bonds goes up. An interesting thing is happening, though, when we look at today’s yield curve (the blue one). It’s not quite as upward – curving. It has basically undergone, in investment geek parlance, a “flattening”.

These rates can be tracked on a graph. The resulting plots of data over a range of years are called the ‘Yield Curve’. It’s easy to see where the yield curve gets its name when you look at the red and green curves on our chart (July 2017 and July 2016 curves). As maturities lengthen, the yield on these bonds goes up. An interesting thing is happening, though, when we look at today’s yield curve (the blue one). It’s not quite as upward – curving. It has basically undergone, in investment geek parlance, a “flattening”.

Yesterday, a client asked me why the rate on his home equity line has increased so much, when mortgage rates don’t seem to have gone up as significantly. That’s actually a result of this flattening. You can see where the shorter yields have increased over the last year, but the 30-year yield hasn’t really budged. Another way of looking at it: In July of 2017, the difference in yield between the 10-year Treasury and the 2-year Treasury (we call it ‘the spread’) was .94%. Today, that spread is only .30%.

In some situations, this flattening continues until the shorter-term yields actually become higher than longer-term yields. This is called a yield curve ‘inversion’. Economists look cautiously at such situations, since inversions quite frequently show up just before recessions (periods when the economic output of the country shrinks instead of grows). In fact, the past seven recessions have been closely preceded by an inversion of the yield curve. It’s probably important to point out that the inversion isn’t the direct cause of the recession – it’s simply the market participants looking into the near future, and being unimpressed with the potential to make money in the market. Unlike in a normal environment, where they need to be rewarded for locking down their money for a longer period, an inversion tells us that, for whatever reason, investors are okay with holding their money in the safety of longer-term government bonds, and don’t feel they need to be rewarded for it. This implies that they don’t see better options for the money in the near future.

The flattening we’re seeing now could be the result of a number of things. First off, the tax cuts that began this year will have a limited effect and the new cash on corporate balance sheets won’t be there forever. The ability for corporations to write off big equipment expenses has also driven the economy, but this won’t be sustained forever. Meanwhile the Fed interest rate hikes create a headwind to corporate profitability by increasing the cost of capital. The low unemployment rate could also limit our ability to grow, as there might not be enough labor available to continue the growth rate we’ve seen over the last year. The working age population is growing at its lowest pace in most of our lives.

Not every yield curve inversion is followed closely by a recession, and most recessions don’t impact the market nearly as severely as in the financial crisis of 2008. Additionally, there are assets that typically do better than others during recessionary periods, so there’s always a place for prudent investing. The economy is still strong and growing, but we’re keeping an eye to the sky, looking out for distant storm clouds.

Meanwhile, regardless of the color of your socks, you’ll owe more interest on the longer loans for the time being.