The January Effect

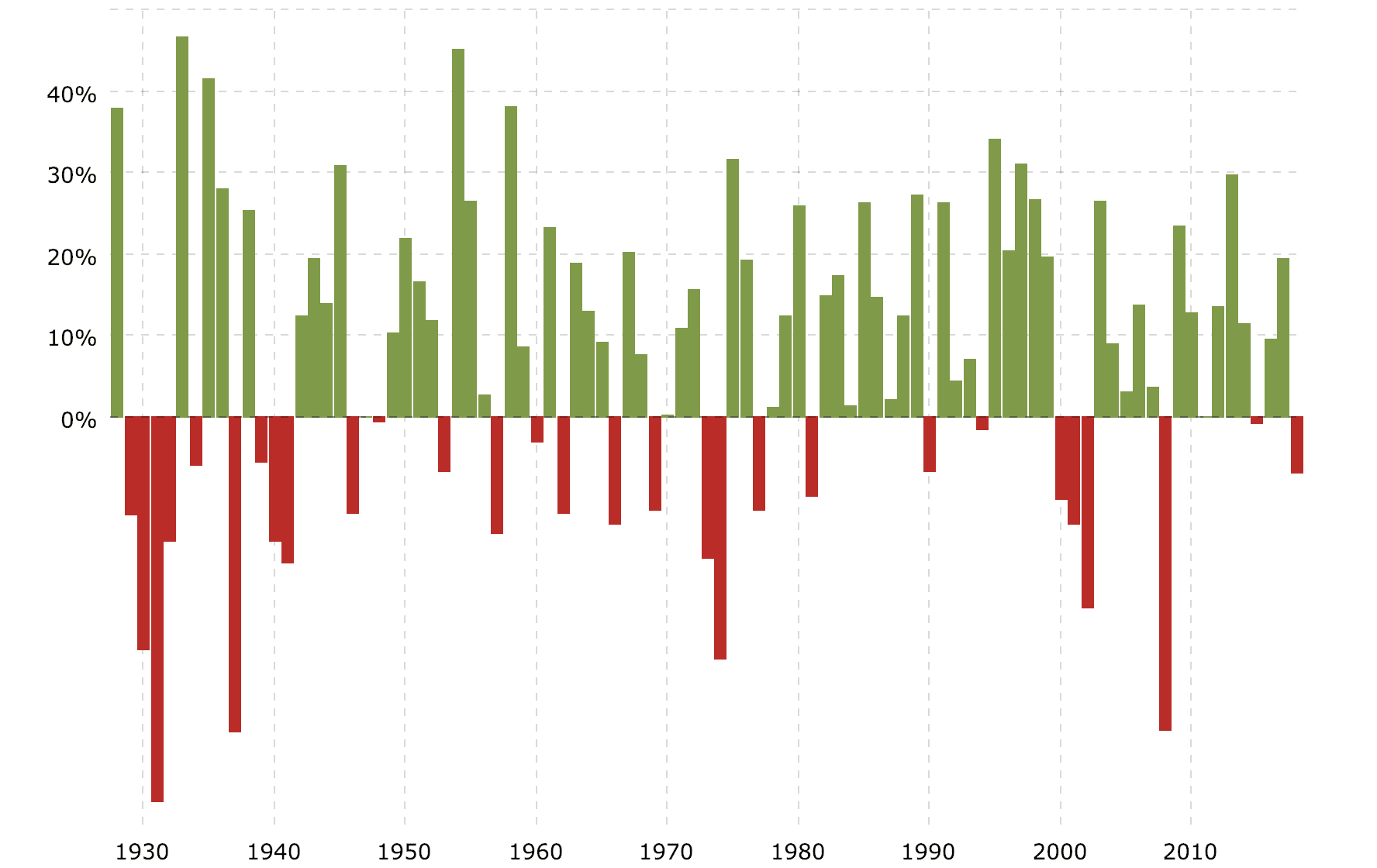

This is the last blog post for 2018, and barring a really nice New Year’s Eve rally, most of the stock market indicators, both domestic and foreign, will likely end up with losses for 2018. Importantly, absent a really rough New Year’s Eve rout on the markets, the stock losses will be far less severe than some infamous recent years such as 2008, 2002 and 1974.

S&P 500 Returns since 1930

Image Source: macrotrends.net

Image Source: macrotrends.net

Inasmuch as the downside volatility this year can’t really be called ‘extreme’ or ‘out-of-the-ordinary’, there actually is a trait that 2018 may be remembered more infamously by, and that’s the fact that it was hard to find winning investments ANYWHERE this year. Ned Davis Research breaks markets into a number of asset classes, including domestic stocks, foreign stocks, bonds, real estate and commodities. By their accounting so far this year, you’d need to go back to 1972 to find a year when it’s been nearly impossible to find positive returns in ANY of these categories. Even during really bad years in the stock market there tends to be a silver lining. In 1974, commodities provided good returns. Real estate did really well in 2002 and in the global financial crisis of 2008, US Treasuries rallied.

After a real ‘bummer’ of a year, some are finding hope in a theory called the “January Effect”.

Discovered by an investment banker by the name of Sidney Wachtel in 1942, the January Effect is a phenomenon studied by analysts where stock prices increase, on average, more in January than in the other months. One study that analyzed data from 1904 to 1974 concluded that the average return for stocks in January was up to 5 times that of other months.

The rationale given for the bump in January seems to make sense. First of all, there is often tax-loss selling during the month of December. Since taxpayers have to be out of a stock for 30 days in order to realize a tax loss, they often buy the stock back in January, and enough of this activity could push stock prices up. Another force is that fund managers often have to report on holdings in their portfolios at year-end, and don’t want to be showing holdings that may be considered risky or out-of-favor. They will replace these with better known stable companies (a practice known as ‘window dressing’), and then buy back into the riskier assets (often smaller companies) again in January. Another possible cause is the fact that many Wall St. firms pay out bonuses at year-end and there are more dollars being funneled into the market at that point.

It’s important to point out that the continued existence of a “January Effect” in the stock market is very much a debated topic. Even analysts who acknowledge that these forces can drive up asset prices in the new year question whether there is a way to take advantage of this effect after the forces of taxes and transaction fees are figured into the equation. Two possible reasons that the January effect is harder to nail down: First, as the effect became more “conventional wisdom”, investors tended to purchase in anticipation of the effect, driving more money into markets in December (creating what started to be known as a ‘Santa Claus rally’. Second, more assets are being invested in tax-deferred plans like 401(k)s where there isn’t the incentive to sell at a loss in December, removing a major component in the January effect.

It will be interesting to see if there is better performance in January 2019. Two things of interest: One is that the effect seems to impact smaller companies more strongly – and there are some indicators that smaller company stocks have been driven down more than larger companies, relative to their earnings. Also, some studies have shown a stronger January effect in the third year of a president’s term.

Another closely watched phenomenon is called the ‘January Barometer’, where a significant positive correlation has been measured over periods of time between the S&P 500 index’s performance in January, and its direction for the remainder of the year. Simply put, someone who puts faith in the January barometer would say “As January goes, so goes the rest of the year”. Importantly, though, there have been some notable detractions from this. 2016 started with a downturn in January and turned into an up-year for stocks. 1966 and 2001 both marked the end of long declines, and had positive Januarys with downturns at the end of the year. Oh, and this year, January saw a 5.6% increase in the S&P 500. Assuming the market closes down, it will be another example of the January barometer not being a perfect indicator.

With any luck, 2019 starts with a fine example of a ‘January effect’, and that creates a nice barometer for the remainder of the year. We’ll just have to wait and see. Either way, hoping your New Year is, most importantly, Happy and Healthy!