Bond prices and interest rates. Tell me again how that works?

In the world of investing, nothing seems to create more puzzlement than the relationship between bond prices and interest rates. It doesn’t help that there are so many different types of bonds and plenty of confusing lingo. When I hear on the radio that the ‘yield on the 10 year came in by 2 basis points’, or ‘the 30-year bond is catching a bid’ – what in the world does that mean? If I’m a bondholder did I just make money? Or, lose money??

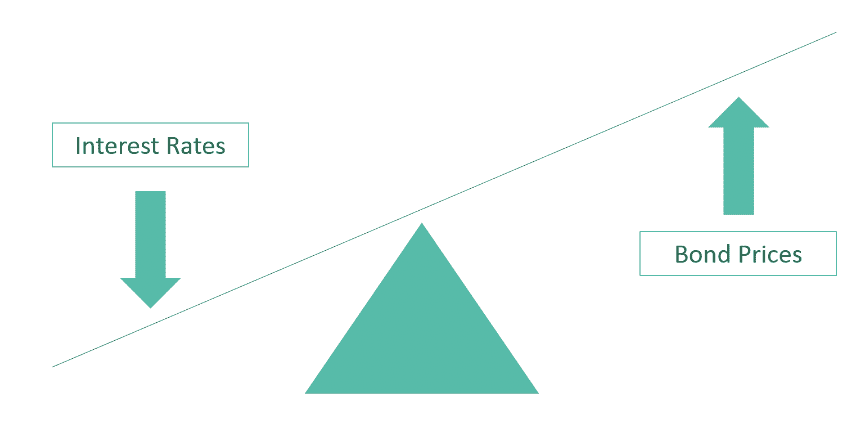

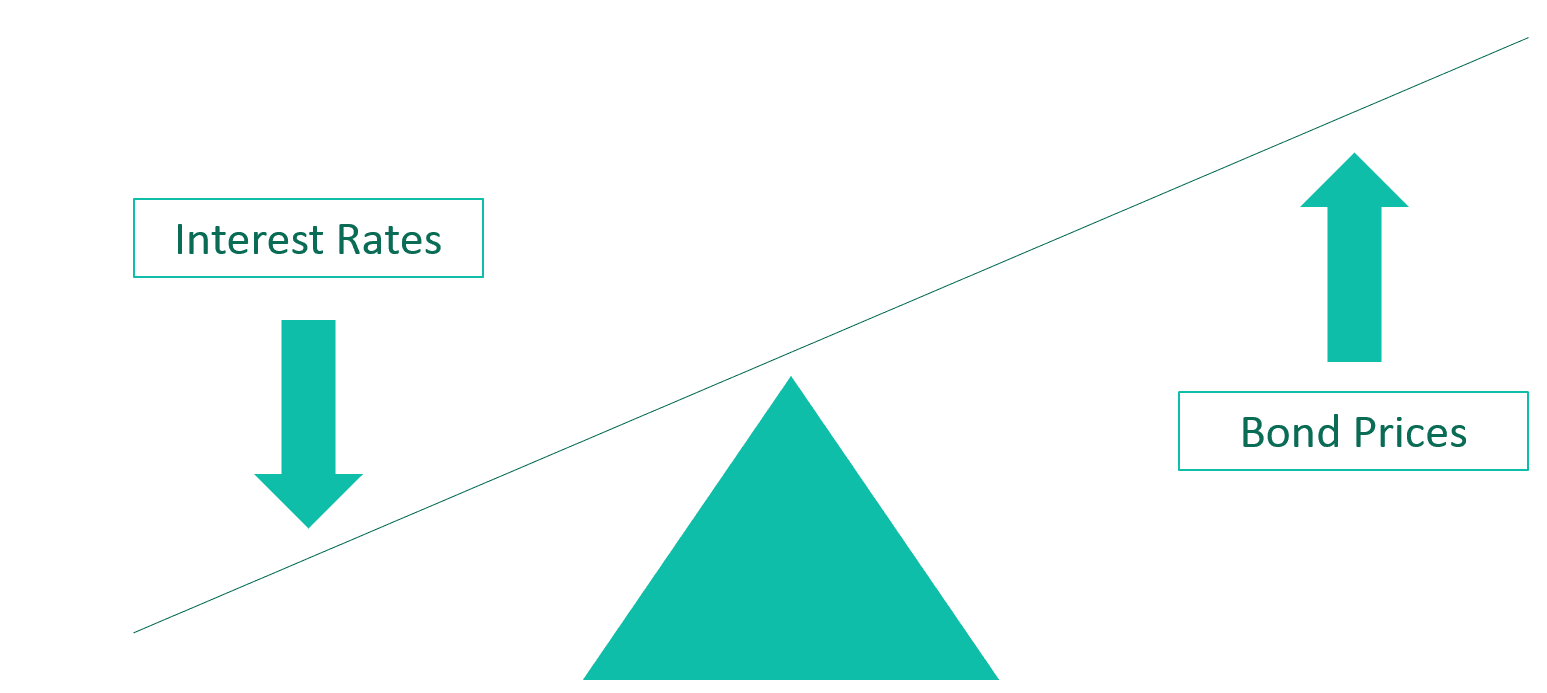

This blog, summarized into one sentence is as follows: Bond Yields and Bond Prices move in opposite directions.

Most people already know that – or they remember that they’ve been told that before. The question is: WHY do bond yields and bond prices move in opposite directions?

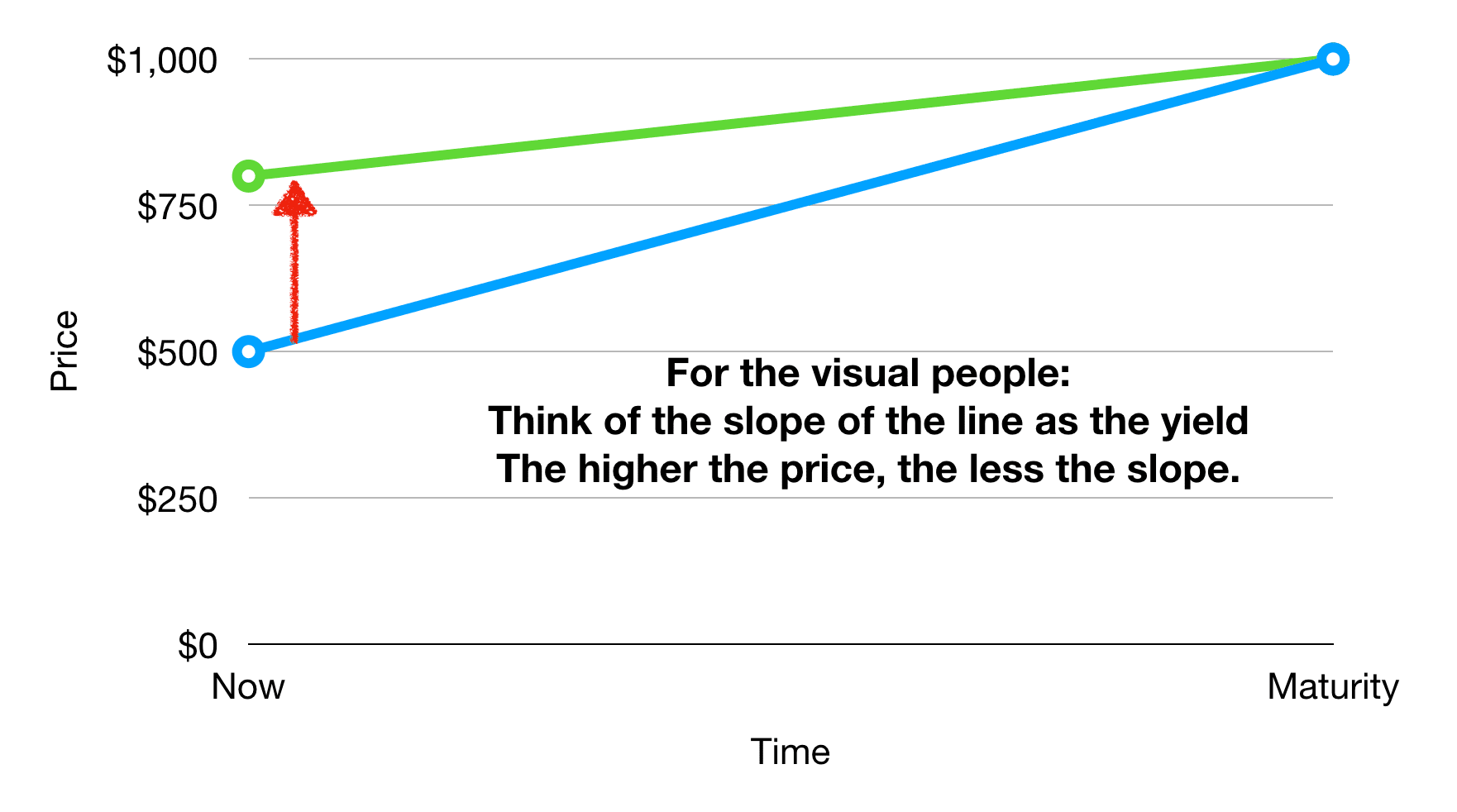

Essential to understanding this dynamic is remembering what, exactly, a bond is. A bond is simply a promise by someone to pay you a certain amount in the future. My Treasury Bond maturing in July of 2020 is a promise by the federal government to pay me $1,000 in July of 2020.

Let’s say I paid $950 for that bond. That means that when I get my $1,000 at maturity next year, I’ll have made $50 on my $950 investment. Dividing $50 by $950 gives me my return as a percentage of my investment. $50 ÷ $950 = .0526, or about 5.3%.

But what if that bond became REALLY popular? So popular that, instead of $950, someone was willing to fork over $980 for that same bond. That investor will make $20 on their $980 purchase. So their return will be $20 ÷ $980 = .0204, or about 2%.

When the price went UP (from $950 to $980), the return (the yield) went DOWN from over 5% to 2%.

The fact is that the more desirable a bond becomes, the higher the price and the lower the yield. Bonds that decrease in value increase in yield.

What drives bond prices up and down? Simple answer is the same things that drive any asset price up and down: Supply and Demand. More supply and less demand for any bond will drive the price up (and, you guessed it, the yield DOWN).

So simple… but why do we continue to get confused?? I think it’s mainly a few things:

- People confuse ‘coupon’ with ‘yield’. Many (but not all) bonds pay an interest payment, called a ‘coupon’. This amount is set and declared when the bond is first issued. It generally does NOT go up and down. Since the coupon payments are a part of the overall return to the investor, they become a part of the yield. In the case of my first bond above that yielded 5.3%, if that bond also had a 4% coupon payment, the overall yield on that bond would be the sum of the price yield and the coupon (5.3% plus 4%), or 9.3%.

- People confuse the face value of the bond with the market value of a bond. In our example above, the key point is that two different investors may pay a different price for a bond, especially if they buy at different times. A bond with a face value of $1,000 may trade at levels well above or below that $1,000 price.

- People don’t always buy bonds at issue or sell at maturity. In fact, most bonds are traded during their lifetime. Some are traded numerous times. Even if a bond is purchased on its original issue date and held to maturity (pre-determining the rate of return on that bond), its value will still go up and down over that time period.

Now that we know this relationship, it would seem that a good time to be buying bonds would be during periods when yields decrease – because that’s when prices increase. We would avoid holding bonds when yields increase – because that’s when prices decrease.

As I write this blog right now, the 10-year treasury bond, which matures in 2029, is yielding 2.04 percent. In which direction will it go? Checking in with the experts, I’ve got the forecasts for the upcoming year from two of the largest investment firms out there: Invesco and JP Morgan Chase. One of them says that yields will increase. The other says they’ll go down to zero.

Oh well – I guess even when you understand the math, there’s still plenty of uncertainty out there. How best to handle that uncertainty? That’ll have to be the topic of another blog, but for now, at least we’ve got the relationship of bond prices and yields down pat, don’t we?