Becoming poor on purpose.

99 percent of the time, when clients sit with us and go over their finances, they are happy to see increases in their net worth, and disappointed to see decreases.

Sometimes, however, folks come in with the complete opposite objective. Every once in a while, someone seeks strategies for decreasing their net worth. What follows is a lot of conversation, soul searching and discussion around strategies and the ethics that surround them.

More often than not, the issue surrounds long-term care planning. Since Medicare and most health insurance policies do NOT provide for the non-medical aspects of living, assistance with these needs is generally paid for out-of-pocket. By non-medical, we’re talking about things like dressing, eating, moving to and from the bed and bathing. These are known as “Activites of Daily Living” (ADLs).

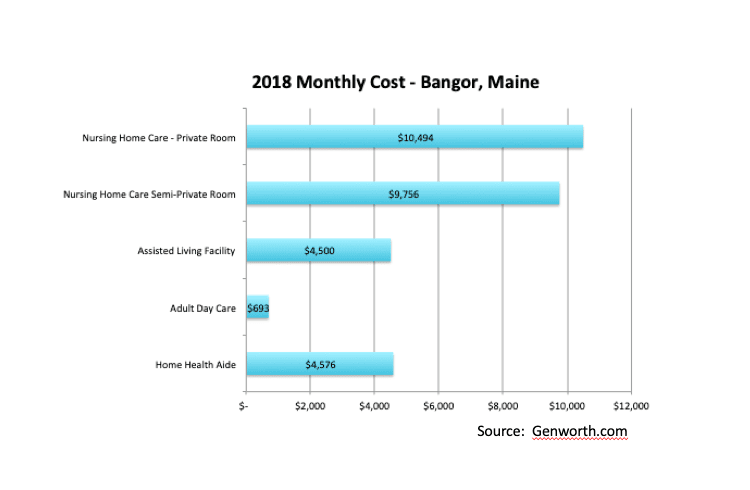

Since these health insurance resources don’t pay for assistance with ADLs, folks have to pay out-of-pocket for this assistance. Even though service providers don’t need to be medically certified, their services can be quite expensive, creating a hardship on many who pay their own way for their assistants.

Despite the high level of cost (especially that of nursing home care), it’s important to point out that this care is available to ALL US citizens, regardless of their ability to pay. Medicaid pays for these services for people who qualify based upon their age, disability, income and assets.

Despite the high level of cost (especially that of nursing home care), it’s important to point out that this care is available to ALL US citizens, regardless of their ability to pay. Medicaid pays for these services for people who qualify based upon their age, disability, income and assets.

While the amount of assets varies from state to state (Medicaid is administered on a state level), in the state of Maine a single person cannot qualify for Nursing Home Medicaid until they have less than $10,000 in assets. In the case of a married couple, the non-applicant can have up to $126,420 in 2019.

With costs of long-term care well above $100,000 per year in many cases, someone with more assets than will qualify them for Medicaid may pay a substantial amount over a number of years, should they require assistance with ADLs or an all-out nursing home stay. This can be a substantial part of the assets they’d worked their lives to accumulate, and it’s especially painful where there is a ‘community spouse’ who is not in need of long-term care, who has to go on with severely diminished assets.

Getting rid of the assets by gifting them to children is tricky, because Medicaid looks back 5 years for any such gifts. The amount of any such gift will offset Medicaid benefits, essentially keeping the recipient in ‘time out’ until those are brought back. For example, if a person gifts $30,000 to a child within the 5-year look-back, and they have otherwise Medicaid-eligible long-term care expenses of $5,000 per month, they will have their benefits delayed by six months to work off the recalled gift amount.

Knowing that there is this ‘look-back’ period and wanting to prepare, sometimes people start a process of ‘artificially impoverishing’ themselves during their retirement years by giving away assets in hopes that a Medicaid claim is outside of the 5-year horizon. This can be tricky, though. If much of the asset base is held in qualified retirement plans, this means taking big taxable distributions to move their ownership of these assets on to the kids. Moving ownership of things like a house to the kids can be tax-disadvantageous as well, depending on how much appreciation has occurred since the original purchase.

And then there are bigger questions: If they are giving a big chunk of their assets away, how will they meet their own living expenses? Will the kids be willing to take on their support and can they be trusted not to have frittered away the assets? Often assets will be placed in trust for the kids with income for health, education, maintenance and support of the parents able to be distributed back to them. Crucial here are two considerations. First, the trust must be ‘irrevocable’ in order for the assets to have been actually ‘gifted’ to the kids. A trust that can be revoked by the grantor is still considered part of their assets. Also, since the transfer is a completed gift, the kids have to acknowledge and have access to the assets.

Finally, there are certainly ethical conversations to be had about such a strategy. Clearly, Medicaid and other programs are there so that people without sufficient assets have something to fall back on. When people who otherwise DO have assets engage in strategies to use these backstop programs, they’re arguably making fewer assets available for those who really needed them in the first place. However, there is nothing illegal about such transfers and ethicists will be able to go back and forth about whether artificial impoverishment is really the thing to do.

It’s important to point out that there are other ways of handling this risk, many of which are less intrusive than artificially impoverishing oneself. Long-term care insurance, while pricy, can be a cheaper solution than incurring the tax disasters that can come about as part of a wealth-transfer scheme. Couples (and singles) who have income needs they want to fill can annuitize assets to create that income stream and lessen the amount of assets they’ll need to chew through to reach Medicaid eligibility. People can buy into progressive care facilities.

All of these options should probably be considered. For some, going broke ‘on purpose’ is an option, but in most cases, it’s likely not the BEST option.