Do you remember where you were on October 19, 1987?

While I can’t put the whole day together in my mind (and while many of my co-workers weren’t born yet), I do recall that I had film class that evening. Cecil B. DeMille’s Cleopatra was the film we were breaking down.

It took a while to get to the subject matter at hand, though. The professor was visibly shaken as he walked into the room. He went on to tell us about how the stock market had crashed that day. He seemed incredulous about the fact that we didn’t even know about this disaster. Blissfully unaware (with no capital assets at risk to our names), we sat, bemused, while our professor ran through all the ways that this was the end of the world.

He probably sat and stewed during the whole film. We forgot about it within the opening credits. Only after I started a financial planning practice focused on working with faculty did I have a full appreciation for what this poor fellow was going through.

As I blog today, it’s exactly 31 years later, and I’m flabbergasted at two things in particular: First, the fact that I’ve been around long enough that my college years were so far in the past. And, secondly, the true magnitude of what happened that day makes me appreciate what our film professor had just experienced.

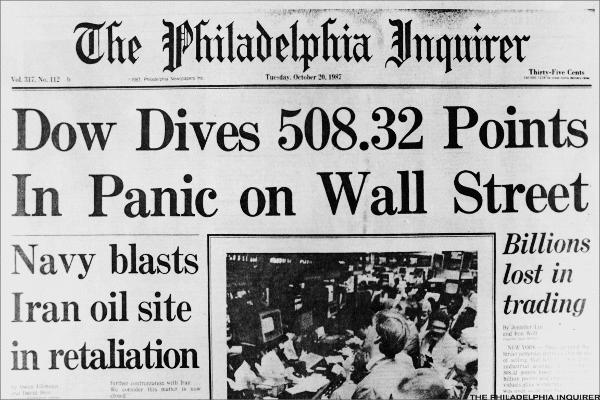

Black Monday, as it became known, was and is a huge event in our collective psyche as investors. The Dow Jones Industrial average declined 508 points that day. To put this into perspective, the “Flash Crash” of 1962, also known as the “Kennedy Slide,” resulted in about 22.6% of value dropping out of the S&P 500 in the first major pullback of the markets after the Great Depression. This took place over the course of about six months. By comparison, Black Monday saw the evaporation of about 22.7% in one day. There was simply no way of putting this event into context.

Another way of putting this into perspective was that this drop, percentage-wise, put into today’s levels, would be approximately 5,700 points worth of decline on the Dow. An 800+ point downward move on the Dow this past week garnered headlines. Kids stuff, by comparison. And US markets were taking part in a global move down. Hong Kong’s market, starting the crash, declined by about 47 percent that day.

Beyond generally high valuations leading up to the crash, the most commonly identified culprit was something called “Program Trading”. The idea that computers operating on algorithms to make buy /sell decisions was a really new thing at the time – and, as a result, it was not well-regulated. Computers sold into the downturn and human traders followed the computers. The resulting spiral downward evaporated a great deal of wealth.

Since Black Monday, curbs, or ‘circuit breakers’ have been put in place to halt trading at certain points when there are really substantial movements in the markets. This is designed to interrupt the cycle that was created when computers and traders played off each other’s movements in the crash. Still, there are indications that technology has the capability of exceeding regulators and market makers. In 2010, the DJIA dropped by over 1,000 points, in a modern day ‘flash crash’. The index recovered nearly all of that in the hour after the decline.

In retrospect, I have a few objective lessons to share on this anniversary of the biggest one-day stock market crash:

- Not everything we experience in the markets has context. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis and other ‘black swan’ events don’t give us an opportunity to assess them in light of similar events. They all do have something in common, though: We’ve recovered from every one of them.

- Valuations are worth looking at. While the crash of 1987 wasn’t directly precipitated by high valuations, other events like the dot-com crash in 2000 likely were the direct result of asset bubbles. And 1987 did feature relatively high valuations in the market. Falling out of a 10th story window hurts much worse than falling from the 2nd story, regardless of what causes the fall.

- Crashes are usually good times to buy. Purchasing ON Black Monday, you’d be fine – up about 13 times your original investment. But even if you purchased the DJIA on the Friday before Black Monday (in other words, you had the worst timing in history), if you continued to hold it today, it’s worth more than 10 times as much – and either way, you’d have collected dividends along the way!

At today’s valuation levels, we aren’t looking terribly over-extended, but we are at relatively high levels. It’s good to take full stock of the volatility you likely face if you are invested in stocks. Diversify well, but still expect that more volatility can come up at any time – and it might come in a form that can’t be compared to anything else. Keep proper time horizons with your investments, and, as Warren Buffet would say, “be greedy when others are fearful and be fearful when others are greedy.”