The Rewards – and Risks – of the ‘Big Relief Bill’

Last week, Congress approved about $1.9 Trillion dollars in additional fiscal stimulus funding, meant to provide greater distribution of COVID vaccines and testing, to increase the amount of unemployment assistance is available to workers, and to put money directly into the pockets of U.S. consumers.

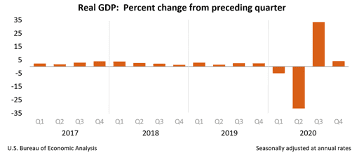

Much of the run-up in stock prices since the 2020 U.S. election can probably be attributed to the markets starting to price in the effect of this stimulus. The CARES act of 2020 gave a pretty good preview of how impactful these programs can be in picking up economic activity. The chart below shows the Q3 impact on real GDP, bouncing back significantly from the economic lockdown in the second quarter.

The Biden administration is not disappointing those who bet on delivery of a substantial relief package. The $1.9 Trillion in relief made it through the House of Representatives and is likely to make it through the Senate, largely intact.

The Biden administration is not disappointing those who bet on delivery of a substantial relief package. The $1.9 Trillion in relief made it through the House of Representatives and is likely to make it through the Senate, largely intact.

It’s reasonable to expect that markets would like such a move. Speeding up the end of the pandemic and putting more money in the pockets of those most likely to spend that money are fundamentally expansive policies.

This money is coming from an increase in debt. The question we as investors face is this: How much will the debt that is created through these stimulus programs impair future growth?

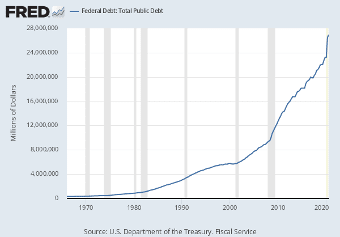

Fundamentally, when our country incurs more debt, it does this by issuing more government bonds. U.S. Treasury Bonds, Bills and Notes are simply debt that the treasury has taken on. Even before the pandemic emergency, the US Government was increasing the amount of debt it had on the books. This is the result of the government spending more on services, defense and debt service than it takes in via tax revenue.

This has pushed the national debt up over $27 trillion dollars, and the amount is poised to grow further. For the first time since the 1940s, the Gross Federal Debt exceeds the Gross Domestic Product, or GDP (which indicates the total amount of goods and services produced by the country).

Seeing the positive impact associated with the stimulus money that is being let loose in the economy, it wouldn’t be an illogical question to ask: why worry about the debt level, when it has such good short-term results?

Seeing the positive impact associated with the stimulus money that is being let loose in the economy, it wouldn’t be an illogical question to ask: why worry about the debt level, when it has such good short-term results?

Most people can intuitively understand the problem high levels of debt create. First, large amounts of debt create large amounts of interest. Money spent on interest doesn’t necessarily stay in the US economy, given that much of the US debt is held by other countries. A higher interest expense leaves fewer dollars for other programs. Revenue can be increased, but this increase comes inevitably from higher taxation and more taxes equals less money for US consumers to spend keeping the economy humming.

The concern here is exacerbated by the fact that more debt doesn’t just increase interest expense in a linear way. If a consumer takes on a large amount of debt at a reasonable interest rate, the rate on future debt becomes more expensive (and even the rates on current debt levels can go up sometimes.). That simply means that a doubling of debt usually means MORE than a doubling of interest expense. As the US debt increases, the argument goes, there is more supply of and less demand for US debt worldwide, and investors must be lured in by higher interest payments.

As investors, high debt levels create concerns down the road for related reasons. Interest rates increasing on government debt can make bonds more attractive to investors. In the current state of affairs, some investment dollars are continuing to chase stocks simply because interest rates are so low. They feel there is no other alternative.

Increasing interest rates also increase the cost of debt for corporations and consumers, and these can slow down consumption and weigh on earnings. This can be a drag on stock prices.

Another impact on stock prices comes with the ‘discounting effect’. When you purchase a stock, you’re essentially buying the future earnings of that stock. Earnings you’ll get years from now need to be discounted back to a present value, using a reasonable discount rate (because you could put that money elsewhere and earn money on it instead of putting out there hoping for income down the road). The higher the discount rate (because other investments like bonds and savings are earning more), the greater the future earnings are discounted, lowering the fair value of a stock.

All of these issues bring down stock values. So, what about buying bonds?

Unfortunately, increasing interest rates also can impact bond values as well. You can read my Geeky Bond Math blog but understand that interest rates and bond prices tend to react inversely. If you hold a bond returning a certain amount of interest, while new bonds being issued have a higher rate of interest, there will be less market value in your bond – investors would rather buy the new one, unless you reduce the price of yours.

So, are we in for bad times ahead, given the amount of debt we’re taking on?

This is tough to say for sure. In the past, there have been periods when markets have done quite well and where economic growth has been sustainable after significant deficit spending initiatives. One argument put forth by the more optimistic camp is that the increased economic activity being created may generate enough additional revenue to the government that it is able to handle the debt interest and even eventually pay down some of the existing debt.

On the other hand, there are those who are concerned that brisk increases in economic activity can lead to a scenario where more demand than supply for goods and services leads to inflation. In this scenario, the Federal Reserve increases rates to pull money out of the system, bringing inflation in check but raising rates in the meantime.

And flipping back to the hopeful side of things, there are those who see inflation as less of a concern, because they feel that advances in technology have led to equivalent advances in productivity and that goods and services can keep up with demand, staving off inflation while the economy continues to grow.

Not knowing how this round of stimulus will end, it’s important to be prepared for just about anything. Investors shouldn’t be putting all of their eggs into the baskets of some investments that have done really well over the past years. If the US Debt level leads to higher interest rates, the high-flying growth stocks of recent years may not be as attractive, since most of their value lies in future growth (which needs to be discounted back to present value). Long-duration US government bonds, which have yielded nice returns over the past few years, would likely see some downside to their value if interest rates were to increase.

The market gyrations associated with the last week in February reflect people taking some of these concerns into focus. Whether or not they are warranted is still to be seen. Now, more than ever, investing with a forward-looking approach is important. Holding some amount of less interest-rate sensitive stocks, bonds, and other types of investments is always prudent and could help to cushion any longer-term volatility this short-term boon to markets may kick up!