The stock market isn’t the economy, and the S&P 500 isn’t the stock market.

Even if the Dow Jones Industrial Average is what people refer to when they talk about ‘the market’. The Standard and Poors 500 index has long been the ‘go-to’ measurement of the US stock market. More frequently on the ‘serious’ finance media, ‘the market’ that is referred to is the S&P 500.

Even if the Dow Jones Industrial Average is what people refer to when they talk about ‘the market’. The Standard and Poors 500 index has long been the ‘go-to’ measurement of the US stock market. More frequently on the ‘serious’ finance media, ‘the market’ that is referred to is the S&P 500.

The rationale is simple: The S&P 500 measures performance of 500 US companies, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average only measures performance of 30 companies.

If 2020 has taught us anything, though, it’s that indices like the S&P 500 aren’t necessarily a representative gauge of the US economy. At the end of the 3rd quarter, with gross domestic product still down significantly, the S&P 500 was actually posting gains on the year.

Actually, the S&P 500 doesn’t really reflect the majority of stocks in the US. It is estimated that 6,000 stock names trade publicly on the US stock exchanges. In addition to the S&P 500, Standard and Poors creates other indexes, including the S&P Midcap 400 and the S&P SmallCap 600. Added all together, they make up the S&P 1500, an index that more stock portfolio managers are tending to use as their benchmark.

A key thing to understand about the S&P 500 index is that it is ‘Market-Cap weighted’. Market capitalization is pretty simply the number of shares outstanding multiplied by the company’s share price. A company with 1 million shares outstanding and whose share price is $35 has a market capitalization of $35 million. The weighting a company has in the index is its market cap divided by the market cap of the entire S&P 500. Thus, companies whose shares make up more of the value in the index will move the index more substantially than those whose shares make up less of the value.

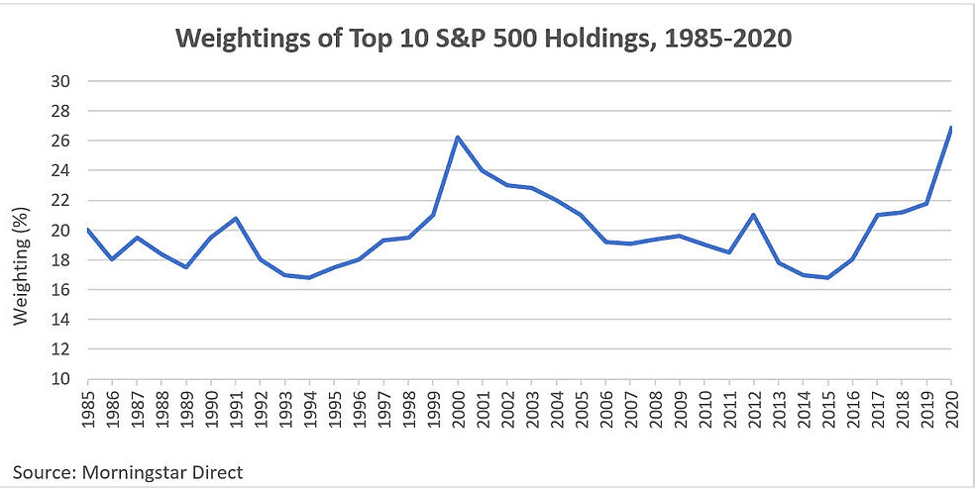

This trait of the index has caused some interesting dynamics in recent months and years. People watching the S&P 500 are often surprised recently at how well it’s done relative to stocks they may own. As of this past August, three companies (Microsoft, Apple and Amazon) made up over 16 percent of the S&P 500’s market cap weighting. In fact, over 26 percent of the index was made up of only 10 of its names. This is a level of concentration we haven’t seen since just before the ‘dot-com crash’ of 2000.

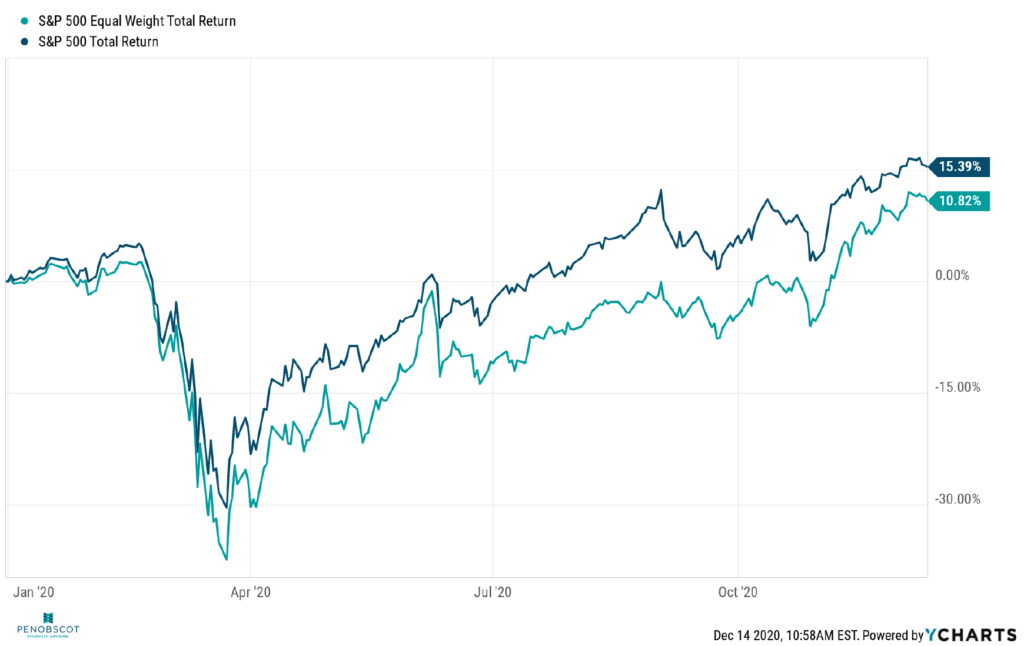

Since mammoth technology companies (and online retailers like Amazon) were not significantly impacted by the COVID 19 lockdowns in 2020, their performance well exceeded that of the majority of their peers. As a result, in 2020, the S&P 500 index significantly has outperformed the average return of its 500 constituent stocks (represented below by the S&P equal weight index).

Since mammoth technology companies (and online retailers like Amazon) were not significantly impacted by the COVID 19 lockdowns in 2020, their performance well exceeded that of the majority of their peers. As a result, in 2020, the S&P 500 index significantly has outperformed the average return of its 500 constituent stocks (represented below by the S&P equal weight index).

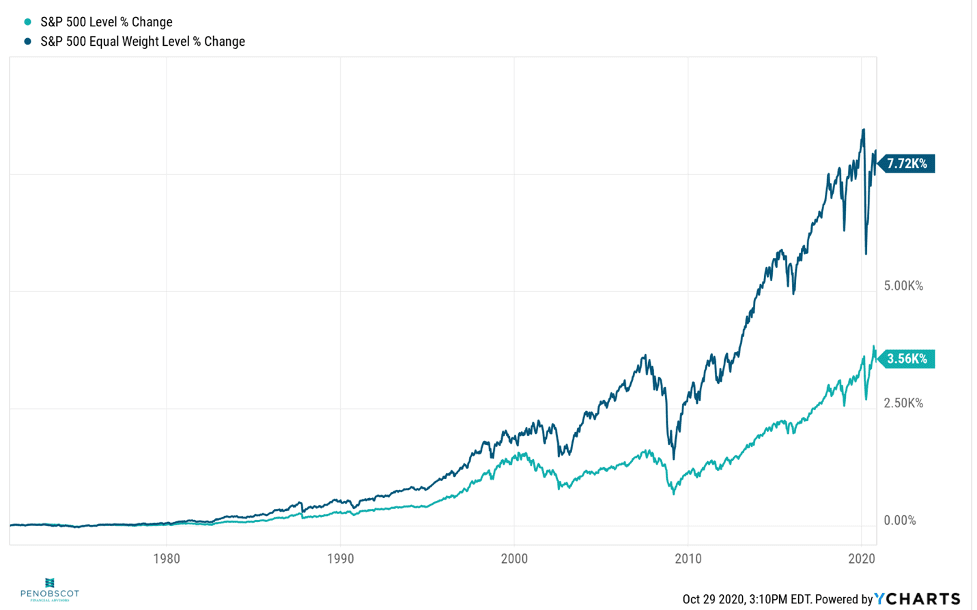

But before you pile all of your money into the parts of the S&P 500 that have generated most of the index’s returns in 2020, it’s helpful to remember that this dynamic of the index generating more returns than those of its average company – it doesn’t hold true historically. In fact, if we track performance back to 1970, the average S&P 500 stock has outperformed the S&P 500 index substantially

But before you pile all of your money into the parts of the S&P 500 that have generated most of the index’s returns in 2020, it’s helpful to remember that this dynamic of the index generating more returns than those of its average company – it doesn’t hold true historically. In fact, if we track performance back to 1970, the average S&P 500 stock has outperformed the S&P 500 index substantially

Exactly what the dynamic is that causes this is unclear. It could be that smaller companies tend to do better over time, simply because they have more room to grow. It’s hard to imagine a company the size of Apple being able to grow at previous rates, given that most of the world is already blanketed with their products.

Exactly what the dynamic is that causes this is unclear. It could be that smaller companies tend to do better over time, simply because they have more room to grow. It’s hard to imagine a company the size of Apple being able to grow at previous rates, given that most of the world is already blanketed with their products.

Today, as I write this blog, Tesla is becoming part of the S&P 500 index, and this will likely represent even greater concentration in the top 10 holdings for the index. With soaring valuations on these technology companies, one might do well to heed some of the lessons that came with the year 2000 rout in technology stocks. It would be foolhardy to assume we are in the same place as we were back then, but carefully diversifying to include smaller companies and stocks of companies based outside of the United States (representing about 45% of total global market capitalization), could be a prudent strategy and could allow investors to benefit from the recovery instead of putting all of their chips on companies who had nothing to recover from!