Why can’t I get much return on safe money?

“I am more concerned with the return of my money than the return on my money.”

Will Rogers

Two things seem to occur pretty reliably during periods of market stress and uncertainty: People become very interested in safe places to put their money, and the return on safe assets drops substantially.

Why is it that at the very time most people want to move to safe assets, the returns seem to be lowest? Is life simply unfair?

Two things explain this phenomenon: Supply and demand – and monetary policy.

At a consumer level (meaning, ‘for you and me’), the rate we get on our savings is largely determined by simple economics, and the principles of supply and demand. In this case, what’s in demand is interest. The price of that interest can be calculated as 1/interest.

For example, if the interest rate is 5%, the price of a dollar’s worth of annual interest is 1 divided by .05, or $20. If the interest rate is 1%, that price is 1 divided by .01, or $100! The higher the interest rate, the cheaper the ‘cost of interest’.

When there’s less demand for safety assets (when people aren’t scared of the ‘markets’), the price of ‘safe interest’ goes down. This is achieved through higher rates of interest. But this nice, safe interest gets more expensive as demand goes up, driving interest rates down.

Back to economics 101, while demand can change prices, so can supply. The supply of money is largely controlled by the Federal Reserve and as is the case in most things, if we increase the supply of money (or anything else), the price will go down if demand remains the same. A decrease in supply (scarcity) makes things more expensive.

‘The Fed’ often acts to increase monetary supply in stressed times like these, effectively lowering interest rates. This results in lower borrowing costs, because if banks don’t need to pay out as much interest, they don’t have to loan it out at as high a rate to stay in business – plus there’s more money now to loan.

Beyond providing liquidity for market disruptions like the COVID-19 shutdowns, the Fed focuses heavily on managing inflation.

Inflation Pros and Cons:

Too much inflation is a bad thing, because it devalues our currency. In a high inflation environment, a dollar a year from now won’t buy what it can buy today.

But deflation (the opposite of inflation) is even worse. Deflation is when prices of goods and services decrease over time. The big problem with deflation is that people aren’t likely to want to buy something today if they think it will be cheaper tomorrow. Deflation on its own decreases demand, and the decrease in demand drives prices even lower. That cycle can be hard to get out of.

So, the Fed works diligently to have neither too much money in the system (hyper-inflationary) nor too little (deflationary).

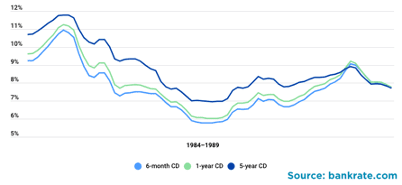

Periods with higher inflation, like the late 1970s and early 1980s are usually also periods of higher interest on bank deposits. This is because demand goes down for low-interest savings (people aren’t cool with losing purchasing power on money in the bank), and, well, by now you know… less demand = lower price of interest = higher interest rates.

And that leads to a closing point: Generally, there isn’t much difference between bank deposit rates and the rate of inflation. Simple supply and demand laws make this so. Actually, most savings and checking accounts pay less than the rate of inflation. In fact, as of the date of this writing, inflation exceeds 1.2%, and savings accounts and short term bonds are yielding well less than that. Saving for a new car that costs $20,000? You’ll need to put more than the present cost of the car in the bank if your savings aren’t keeping up with the inflating cost of the car. Suddenly, FDIC-insured assets seem risky!

And that leads to a closing point: Generally, there isn’t much difference between bank deposit rates and the rate of inflation. Simple supply and demand laws make this so. Actually, most savings and checking accounts pay less than the rate of inflation. In fact, as of the date of this writing, inflation exceeds 1.2%, and savings accounts and short term bonds are yielding well less than that. Saving for a new car that costs $20,000? You’ll need to put more than the present cost of the car in the bank if your savings aren’t keeping up with the inflating cost of the car. Suddenly, FDIC-insured assets seem risky!

How do you avoid losing purchasing power?

- Research banks and be open to using online banks who often pay higher interest rates on deposits.

- Reap ‘illiquidity premiums’ by taking advantage of higher rates on things like CDs, government bonds, and fixed-rate annuities. For assets you don’t need to touch immediately, this premium can give you a boost above the rate of inflation.

- Accept some credit or volatility risk by investing in municipal or corporate bonds or mortgage-backed securities.

It should go without saying that times of market stress are not usually good times to be taking risk assets off the table and moving them to ‘safety’ assets. The reality is, however, that people pay a lot more attention to the safe assets at times like these. Be careful not to turn safe assets into losers by locking in losses on risky assets or by earning less than the rate of inflation!