Breaking the Financial Rules of Thumb

I’ve never been a big fan of ‘Rules of Thumb’. They inevitably cause angst for people who have no need to be anxious, or they provide a false sense of security to people who SHOULD be worried.

I’ve tried to research the etymology of the phrase ‘Rule of Thumb’ and it’s not helping. There are a lot of references to a rule in old England that the switch a man uses to ‘correct’ his wife may be no wider than his thumb. Just more reason to toss the phrase onto the rubbish heap.

And admittedly, as an efficiency enthusiast, rules of thumb DO come in handy sometimes. But it’s when they’re applied to something as important as your finances that I think we need to throw them out entirely.

Here are a few:

“You need to keep 3-6 months of income (or expenses) in cash”

This has been a staple of financial advisors since time began. It makes perfect sense that some of the money we set aside should NOT be subjected to things like market risk and barriers to access. Having money in the bank is nearly universally a good thing. Too little money in the bank is not a good thing. Too much money in the bank may not be optimal either.

How much is the right amount? It’s going to be very different from person to person:

Mark is a tenured faculty member at the University. Mark rents an apartment that he’s been in for 5 years. Mark is single, with no dependents. Mark leases a late model car, which he drives to work on the rainy days – otherwise, living close to the University, he usually takes his bike. Mark routinely reviews his insurance coverage with his advisor and is in fine health.

Lisa is a business owner. Her income arrives in fits and starts from a small number of key clients. She has 3 children and is a single mom. One of her kids has a medical condition that often results in large out-of-pocket expenses. Lisa owns a house and an aging car. She buys a high-deductible health plan from the ACA website.

What should be clear is that Mark and Lisa have vastly divergent needs for cash reserves. It’s hard to imagine Mark needing to come up with cash on short notice. 3 to 6 months of income (or expenses) might be substantially more than he needs. Why have that much money sitting in very low-yielding cash? Lisa, on the other hand might have a need for substantially more than six months in cash just to account for her uneven income numbers and the large number of things (medical expenses, house repair, car repair, etc…) that she may have to pay for at any given time.

“Subtract your age from 100 to determine the stock allocation in your portfolio”

A few factors determine the appropriate allocation for your portfolio:

-

- Your WILLINGNESS to take risk

- Your ABILITY to take risk

- Your tax situation

You’ll notice that age isn’t on that list Someone who is retiring next year at the age of 65 still has a long time horizon in front of them (hopefully). I’ve found that, assuming the ability to take risk doesn’t change later in life (because of the ongoing income need that is being funded), it’s the willingness to take risk that drives investment decisions the most. I’ve also found that risk tolerance changes very little over the course of a long lifetime.

A 70-year-old, risk-tolerant investor who has to fund her retirement for the next 20-30 years is likely to sell herself short if she gets too conservative. Likewise, a 25-year-old should be in a conservative investment mix if his risk tolerance makes him likely to sell out on the first downward movement.

“You need seven to ten times your income in life insurance”

For some reason, life insurance remains a widely misunderstood financial tool. Simply put, life insurance provides for the needs for survivors and dependents when someone has died (and thus the economic value of the person’s future income has been lost).

Simply put, someone who doesn’t have dependents is not likely to have any substantial need for life insurance. Similarly, someone without future earnings potential also lacks a fundamental need to cover this income.

For those who DO have future earnings potential, and people depending upon this, it’s way too big an issue to rely on some simple rule of thumb. Needs can be all over the map and the 7-10x rule might result in someone being significantly over- or under-insured. Actually taking the time to define the needs and to measure the amount of insurance required to meet those needs is vital. Don’t leave this to some arbitrary formula.

“Spend taxable assets first and tax-deferred assets last”

Tax deferral is a great benefit, because assets that would otherwise go to paying taxes can stay in the portfolio, themselves providing gains.

However, some people consider this and take on a ‘defer at all costs’ approach when sequencing distributions.

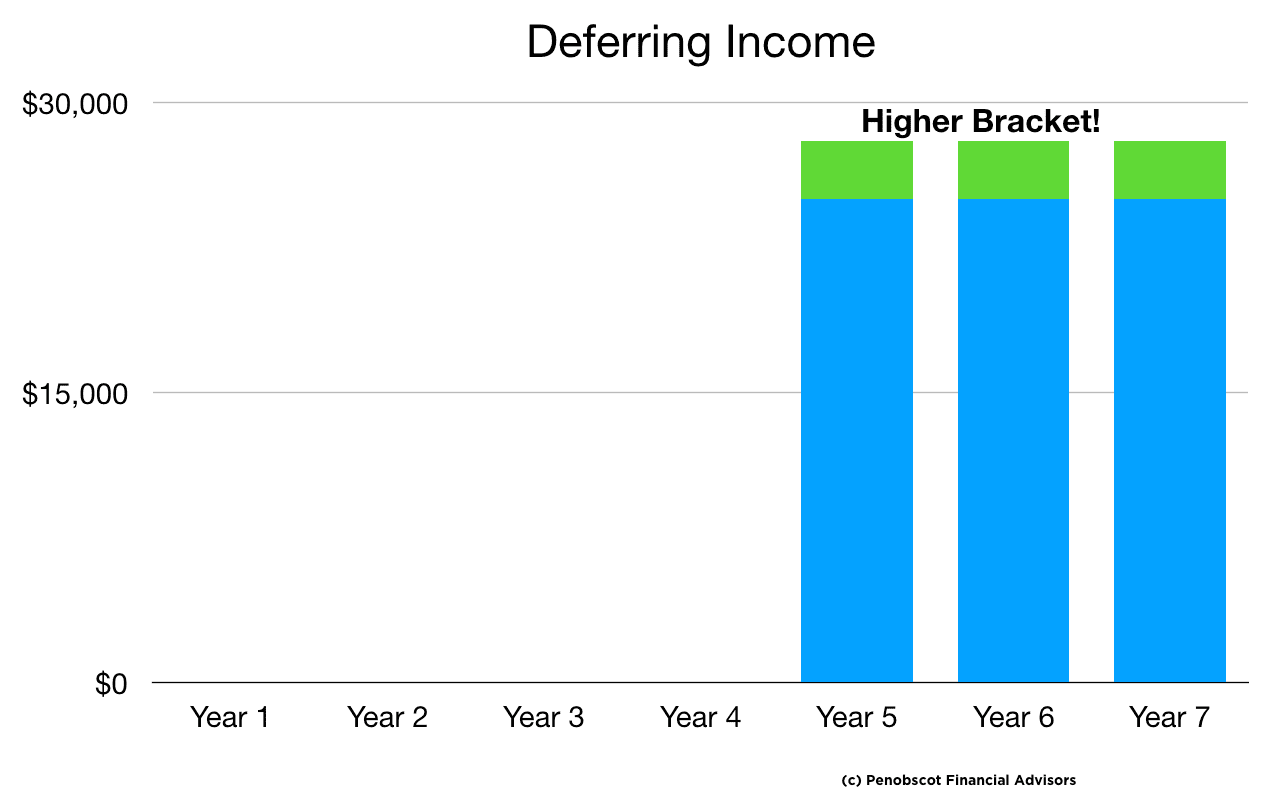

Because of Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) rules, assets WILL have to be distributed down the road. Deferring for a longer period of time can result in higher RMDs, unintentionally putting the asset owner in a higher tax bracket than if they had started before distributions became required!

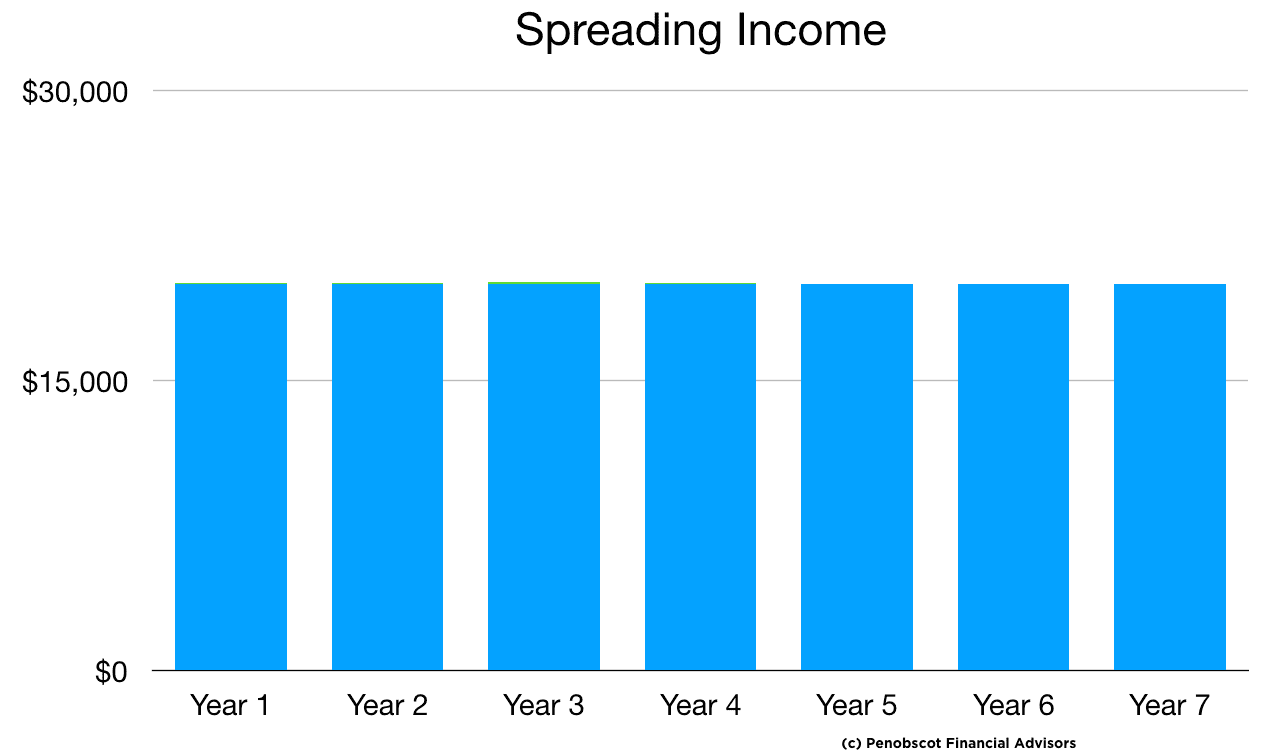

Sometimes, spreading tax-deferred income over a longer period by starting early….

Can prevent going into a higher tax bracket later on!

Here’s a great rule of thumb: When you’re making important financial decisions, don’t use rules of thumb! Take the time, do the math, seek help and get it right!