Retirement Plan Hacks to ‘Flatten the Curve’

‘Flattening the curve’ is sure to remain a major part of our lexicon long after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed. Curve flattening makes the assumption that simply eliminating the disease is impossible. As such, the next most important step is to slow the spread so as not to overwhelm the medical community’s capacity to treat those who fall ill. A longer epidemic duration is acceptable as long as too many infections do not occur all at once. We don’t want to break through the line where there are more in need of critical care than beds to accommodate them.

‘Flattening the curve’ is sure to remain a major part of our lexicon long after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed. Curve flattening makes the assumption that simply eliminating the disease is impossible. As such, the next most important step is to slow the spread so as not to overwhelm the medical community’s capacity to treat those who fall ill. A longer epidemic duration is acceptable as long as too many infections do not occur all at once. We don’t want to break through the line where there are more in need of critical care than beds to accommodate them.

When planning retirement income, a similar objective frequently arises. Taxes have usually been deferred on a significant portion of client assets, by way of deductible contributions to retirement plans and IRA accounts. Eliminating these taxes is impossible, so we look to achieve the next-best objective of avoiding excessive income tax burdens on these distributions. We don’t want to break through the line that puts us in a higher tax bracket.

Under the vast majority of retirement plans, we can only defer taxation up to a point during our lives. Distributions (and taxation) become mandatory eventually, either upon the latter of reaching age 72 (up from 70 ½ as a result of the SECURE Act of 2019), or upon retiring.

“Younger” retirees with pools of assets elsewhere, or with relatively modest spending needs, will inevitably lean toward deferring taxation on their retirement accounts for as long a period as possible, putting distributions off until they’re absolutely required. What often happens is that the assets continue their tax-deferred accumulation for an extended period, and when Required Minimum Distributions start, they can be substantial. The larger the retirement plan distribution, the more likely clients are to find themselves in a higher tax bracket later on in retirement than they were earlier.

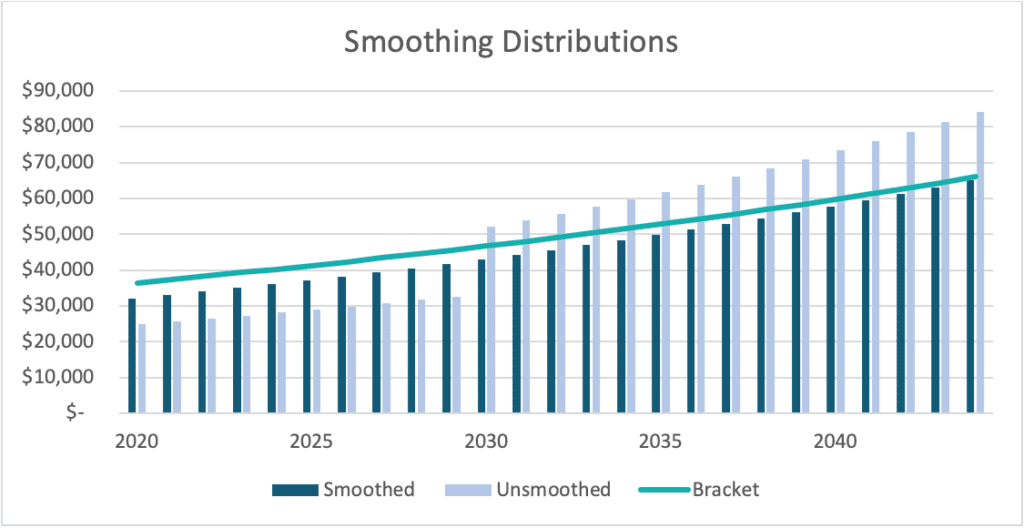

One way of tackling this issue is to ‘smooth out’ retirement distributions. This involves the relatively counter-intuitive step of taking taxable distributions from tax-deferred retirement plans earlier in retirement, often long before distributions are required!

By taking distributions earlier in retirement, usually to ‘fill up’ the remainder of their tax bracket during the early years, the pool of assets used to figure Required Minimum Distributions ends up being smaller, and RMDs are less likely to push income into a higher tax bracket once they do come due.

Another similar strategy, especially for those who don’t actually need extra income in their early retirement years is to convert IRA assets to Roth IRA. Carefully calculating how much a taxpayer has left in her tax bracket, and converting that amount, can result in lower Required Minimum Distributions later in retirement (since Roth IRA assets are not subject to RMDs and will be non-taxable when distributed or (eventually) inherited.

Even for folks who already have started RMDs (and, remember, in the year 2020, due to the CARES ACT, there are NO RMDs from the vast majority of retirement plans), there are still steps that can be taken to ‘flatten the curve’ and prevent taxation in higher tax brackets. A prominent example is the Qualified Charitable Distribution (QCD). Retirees age 70 ½ and over can distribute contributions to qualifying charitable organizations directly from their IRA and not be taxed on those distributions, up to $100,000 per year. A retiree who wants to support a charity, especially if they otherwise can’t benefit from itemizing their charitable deductions, can often keep themselves below the next bracket by distributing from their IRA instead of from other accounts.

It takes careful planning to make improvements in these areas. Having a solid knowledge of taxation and good modeling software is important. Additionally, annual income is sometimes not entirely in our control. There will be years with larger capital gains and dividends, and tax laws are sure to change from time to time. But, in general, the idea of leveling out income over time, or ‘flattening the curve’, is likely to be a winner when it comes to saving on overall taxes in the long run.