Don’t Under-estimate your Capital Gains tax!

Often, the most disappointed reactions we get from clients is not the result of market declines. Rather, it’s the surprise that happens when they get their tax bill. Frequently, capital gains taxes are to blame.

It’s important to know what causes someone to have to pay capital gains tax. Any time a taxpayer sells an investment, whether a stock or bond, mutual fund, ETF, or tangible property like real estate, she will either get back more than she paid (capital gain) or get back less (capital loss). In either case, there is generally a tax consequence.

Forgetting the new(ish) 20% long-term capital gains tax rate

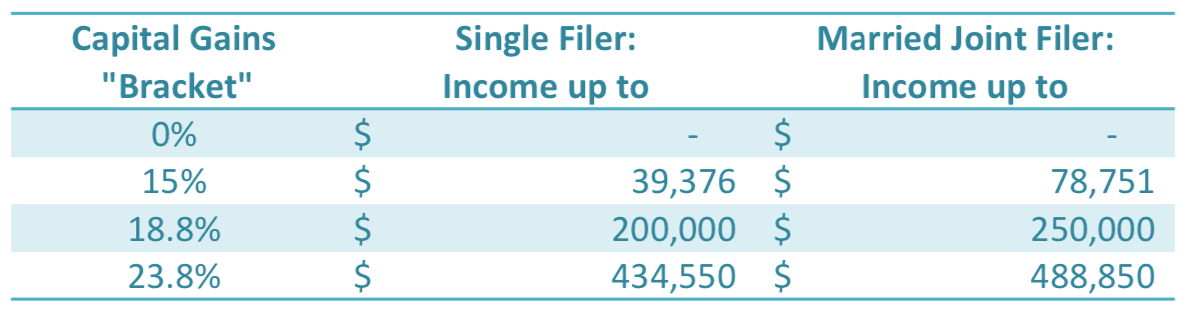

Depending upon how long the investment being taxed is held, the tax might very well be lower than the taxpayer’s income tax bracket. For taxpayers in the 10% and 12% federal brackets, the long-term capital gains tax rate (which applies to investments sold after being held for more than a year) is zero. For most other taxpayers, the long-term capital gains tax rate is 15%. But there’s another tax bracket that some taxpayers don’t anticipate, and that’s a 20% tax rate for single filers who have income over $434,550 in 2019, and for married filers making over $488,850. When the sale of an investment is large, and large capital gains result, often taxpayers don’t remember this relatively new tax bracket, which can apply even if the other income sources are normally in a lower bracket.

Not knowing about the Net Investment Income tax

But even before the higher capital gains tax kicks in, there are additional taxes to be concerned with when it comes to capital gains. One of them is an extra surtax on something called “Net Investment Income.”

Net investment income is ‘unearned’ income – so it doesn’t include wages, self-employment income, unemployment compensation, Social Security benefits, or alimony. Usually Net Investment Income arrives in the form of capital gains, interest, or dividends. It can include income produced by rental properties, capital gain distributions from mutual funds, and even royalty or annuity income and interest on loans you might have extended to others. It includes income derived from a trade or business that is classified as passive income and income from a business trading financial instruments or commodities.[1]

A special surtax, first imposed in 2013 to prop up Medicare, applies to single filers who make over $200,000 ($250,000 for married people filing jointly) and who have this Net Investment Income. This additional tax amounts to 3.8% of Net Investment Income when it gets stacked on top of those limitations.

Combined, the federal capital gains tax is often 23.8% for higher income taxpayers (or those with especially large capital gains during a year).

Oh, and then there’s State Income Tax

To make matters worse, most states with income taxes don’t distinguish between capital gains and any other kind of income. For example, in Maine, where we have a 7.25% state income tax bracket, that amount would be added on top of any capital gains tax applied at the federal level.

For someone selling an investment that they’ve held for more than a year, making the assumption that they’ll just be subject to 15% capital gains tax can lead to disappointment, especially if they’re at a higher income level. Since the combined capital gains and net unearned income taxes at the federal level can easily be 23.8 percent, and states add income taxes on top (Maine, for example adds another 7.25 percent), the actual taxation of a long-term capital gain may be TWICE the baseline federal long-term rate.

Even worse, a taxpayer selling an investment that they held for less than a year doesn’t get to take advantage of a lower capital gains tax rate and still owes the special tax on Net Investment Income. Higher income taxpayers in this case can find themselves owing nearly 50 percent on the taxable gain they’ve realized. The same thing can result from net unearned income that isn’t eligible for capital gains rates, like taxable bond interest.

The taxable impact on other income

Even for people who aren’t forced into the higher tax rates, the inclusion of substantial amounts of unearned income (through taxable gains or dividends) can have the effect of making more of other benefits, like Social Security, taxable, because of something we call the Social Security Tax Torpedo.

On the other hand, sometimes investors are pleasantly surprised to find that they don’t owe ANY capital gains taxes. This can apply to people with smaller levels of taxable income, who only get taxed at the 10% or 12% income tax brackets. To the degree their capital gains income doesn’t push them into income levels above these brackets, their capital gains are completely free from taxation at the federal level (they may still be subject to state income taxes). For these folks, realizing capital gains can be a key strategy! The same can be said of the sale of a personal residence where no capital gains tax is applied to the first $250,000 of gains for a single person, and the first $500,000 for a couple.

Avoid negative surprises

Substantial underpayment of tax obligations can result in penalties and interest, making the tax burden even more of an unpleasant surprise. Thus, it makes sense to consult with your tax advisor when any ‘out-of-the-ordinary’ events happen, such as

- A sale of an investment or investment property

- A large dividend being paid out of an existing investment

- A substantial bonus or incentive payment

- Exercise of stock options

- Anything else that substantially changes your income picture for the year.

Knowing in advance the likely impact of any of these will allow you to set aside, through estimated tax payments, an amount that will cover your obligations, saving the unpleasant surprises in April!

[1] There are some exceptions to Net Investment Income, including tax-exempt interest, gains realized from the sale of a personal residence and gains on property held in a trade or business.