The Great Roth Conversion Debate

One of the first ‘new things’ I encountered in the business came as a result of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. A bill sponsored by senator Bob Roth of Delaware became part of the Act and allowed for non-deductible IRA contributions to be made to a new kind of IRA that would grow completely tax-free.

One of the first ‘new things’ I encountered in the business came as a result of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. A bill sponsored by senator Bob Roth of Delaware became part of the Act and allowed for non-deductible IRA contributions to be made to a new kind of IRA that would grow completely tax-free.

In an attempt to avoid this becoming a big tax-dodge for the wealthy (and an even bigger strain on future revenue to the federal government), income limitations were placed on taxpayers who would be eligible to select the new “Roth IRA”. However, these limitations were significantly loosened later with the “Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act” of 2005. Up until then, taxpayers could convert their existing IRAs to Roth IRAs only if their income (Married filing jointly or Single –didn’t matter) was under $100,000. This limitation went away with the new act, and removed the income limitation for people wanting to convert traditional assets to a Roth IRA.

And so began a long career with hundreds (maybe thousands) of opportunities to assess the wisdom in converting a ‘traditional’ IRA to a Roth. After many years of running the calculations, I can say without hesitation that: IT DEPENDS.

The basic concept of a Roth conversion is simple. Pre-tax assets in a ‘traditional’ IRA that are converted to a Roth IRA are taxed as income in the year converted. After-tax IRA assets, already having been taxed as income, are omitted from taxation. If someone has both after-tax and pre-tax money in their IRA, any conversion must be done pro-rata (taxable and nontaxable, based on the balances in ALL of their IRAs).

There is a conventional wisdom out there: If you will be in a higher tax bracket in retirement, convert your IRA to a Roth IRA. Your conversion at the lower working age bracket will be taxed at a lower rate than at your higher tax bracket in retirement – so pay the taxes now, rather than later.

While that makes sense, it is a woefully incomplete basis for making this decision. First, no one really knows what his tax bracket will be in retirement. No one knows whether her tax bracket might even change in retirement. And, doing the calculations, sometimes it even makes sense to convert if the taxpayer thinks they might be in a LOWER tax bracket in retirement!

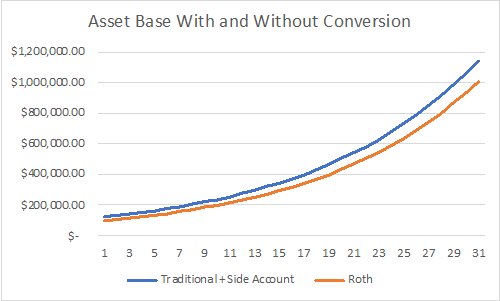

When conducting an assessment of whether or not a taxpayer should convert IRA assets to a Roth IRA, we start with the assumption that money a taxpayer ‘saves’ by NOT converting should be assumed to be invested in some type of taxable ‘Side Account’. As such, we’re comparing apples to apples: A taxpayer who has converted has less money to start, since some of their outside wealth went to paying taxes.

For example, an investor with a $100,000 pre-tax IRA, age 35, is in the 22% income tax bracket. In order to compare strategies, we’ll consider the fact that conversion will cost him $22,000 in extra income taxes, so by not converting, he’ll have the $100,000 in the IRA PLUS another $22,000 to invest in a taxable ‘Side Account’, for a total investment of $122,000. If he does convert, he only has $100,000.

The chart below shows clearly that the investor who doesn’t convert will have more money because they have the ‘Side Account’ whereas the converting investor doesn’t have this extra money. As time goes by, and assets grow (at an assumed 8% rate both during and after retirement), so will the disparity between the two assumed pools of money.

When we get to retirement, the income that can be generated over a set number of years is obviously higher with the non-converting investor – because she has more money to start out with!

When we get to retirement, the income that can be generated over a set number of years is obviously higher with the non-converting investor – because she has more money to start out with!

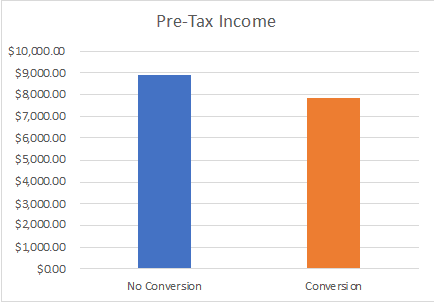

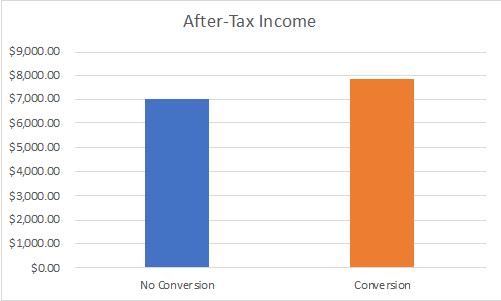

BUT… the monthly AFTER-TAX distributions (the money the investor can actually spend) ends up being HIGHER for the person who converted. In the example charted below, the assumption is that the investor is taking this income in the same 22% bracket as when he was working, and that growth in the accumulated ‘Side Account’ is taxed at the long-term capital gains tax rate of 15%.

BUT… the monthly AFTER-TAX distributions (the money the investor can actually spend) ends up being HIGHER for the person who converted. In the example charted below, the assumption is that the investor is taking this income in the same 22% bracket as when he was working, and that growth in the accumulated ‘Side Account’ is taxed at the long-term capital gains tax rate of 15%.

Even in situations where a lower tax rate is assumed in retirement, the conversion scenario often comes out on top. Variables that determine this include how much lower the retirement tax rate assumptions are, how long until distributions begin, and what the growth rate is during accumulation and distribution periods.

Even in situations where a lower tax rate is assumed in retirement, the conversion scenario often comes out on top. Variables that determine this include how much lower the retirement tax rate assumptions are, how long until distributions begin, and what the growth rate is during accumulation and distribution periods.

An important takeaway is this: Everything you use to determine whether or not to convert (tax rates in the future, rate of return, life expectancy, etc.) is an ASSUMPTION. And assumptions can be very different from reality. Any calculation you come up with to determine whether or not to convert has the potential to go the other way.

When it’s close, I typically recommend IN FAVOR OF CONVERSION. There are a few reasons for this:

- TAX LAWS CAN CHANGE

If you’ve run the calculations using current tax code, keep in mind that this code can change. Actually, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 will largely go away after 2025, absent new legislation. Assuming tax rates in the future go up may not be unreasonable when you consider that the US runs a nearly $23,000,000,000,000 deficit. - OTHER TAXES AND COSTS CAN COME UP

Social Security taxation is based upon something called ‘Provisional Income’ which includes traditional IRA distributions, but not Roth IRA distributions. This can create something called the Social Security Tax Torpedo, which can create much higher effective tax brackets in certain situations. Additionally, things like Medicare can get more expensive through something called IRMAA when traditional IRA income is taken (but is not impacted by Roth distributions.)[1] - RETIREMENT INCOME NEEDS MIGHT NOT BE LEVEL

Most people, when in retirement, have some years when their need for income is higher than others. Buying a retirement property or boat, incurring significant medical costs during a year, helping with a grandchild’s tuition… These are all things that can cause income to ‘spike’ into a higher tax bracket in a given year. Having non-taxable income resources like a Roth can help to keep entering higher brackets during these years. - THERE MAY BE INCOME NEEDS BEFORE RETIREMENT

Sometimes, converting prior to retirement can make assets available earlier than in an IRA, without early withdrawal penalties. For example, if a taxpayer, 40 years old, converts a $50,000 IRA to a Roth, she has to wait 5 years to take any distributions without penalty – but after the 5 year wait is up, she can take all $50,000 without the IRS 10% early withdrawal penalty, even if she is still under 59 ½ years of age. If her IRA is then worth $70,000, she can still take the $50,000 tax-and-penalty-free, but the growth on that money (the additional $20,000) needs to stay in the Roth until she is 59 ½ in order to avoid the penalty. Additional exceptions, including those for first-time homebuyers and people who need to pay for college tuition, make having Roth assets desirable even before retirement.

Since every rule has its exceptions, I’ll throw that there are some situations that make me hesitant to recommend conversion. Most of them involve situations when the IRA holder has charitable intentions. Clearly, it makes no sense to convert an IRA when the intention is to leave it to a charitable beneficiary. Since the charitable organization will not have to pay taxes eventually, there’s no need to pay taxes now on a conversion!

Similarly, IRA holders over 70 ½ are able to utilize the Qualified Charitable Deduction (QCD) and distribute up to $100,000 to qualified charitable organizations income-tax-free while they’re alive! These folks, too, wouldn’t want to convert everything to Roth, essentially losing the opportunity to legally dodge taxes on their charitable giving.

If all of this seems confusing, it is. There is no certain formula for making an unambiguous decision for or against a Roth IRA conversion. You can, however, make sure that the deck is stacked in your favor by taking the time to consider all of the moving parts. Your financial advisor should have tools to make this a little easier, and we’re always eager to help!

[1] Keep in mind this can work both ways: Someone considering a conversion after starting Medicare might want to be careful because income caused by the conversion itself can result in higher Medicare premiums!